Rewriting the Future: How Peace Agreements Can Break the Cycle of Child Soldiering

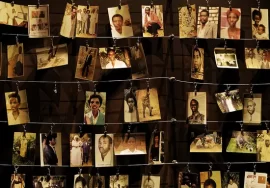

A group of demobilized child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). @L.Rose / Wikipedia.

As the world continues to grapple with the horrors of armed conflict, one of its most heart-wrenching persisting abuses is the use of child soldiers. These children, drawn into combat by force, coercion, or circumstance, endure unimaginable trauma and loss. Yet, in the aftermath of conflict, their plight is often sidelined in favour of political expediency. This oversight not only hampers their reintegration into society but also leaves open the possibility of their re-recruitment. Amid this complex challenge, peace agreements stand out as critical instruments for ensuring both justice and healing.

Peace agreements are not merely tools to halt gunfire—they are blueprints for rebuilding. As I demonstrate in my recent study, peace agreements signed between 1990 and 2022 that directly reference child soldiers number only 77 out of 252 that mention children at all. These agreements contain a total of 189 provisions focused on child soldiers. While this shows progress, the inclusion of child soldier-specific provisions is still the exception rather than the norm.

At their best, peace agreements can address three interlinked phases crucial to tackling the child soldier issue: ending recruitment and use, disarmament and reintegration, and accountability. Each phase, if addressed thoroughly, holds the power to transform former child soldiers into community members with dignity and purpose.

Halting Recruitment and Use

The first step is to prevent the future recruitment and use of children in armed conflict. Some peace agreements have taken bold steps in this direction. For example, the 2008 Magaliesburg Declaration on the Burundi Peace Process explicitly calls on parties to “abstain from all actions that might be perceived as fresh recruitment drives, particularly among children.” Other agreements, such as the Central African Republic’s Libreville declaration, echo this sentiment by banning recruitment altogether.

Importantly, these agreements don’t just stop at declarations. They often integrate provisions into ceasefire terms, making child recruitment a direct violation. Yet, a critical gap remains: While many agreements focus on forced recruitment, fewer address the broader socio-economic drivers that lead children to voluntarily join armed groups. Poverty, lack of education, and the breakdown of communities are fertile ground for recruitment. Hence, peace agreements must go further—targeting root causes and offering real alternatives.

Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR)

The second critical area is disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR)—one of the most tangible ways peace agreements can support former child soldiers. Effective DDR programs do more than collect weapons. They offer psychological support, educational opportunities, and pathways back to civilian life.

Some agreements show promising practices. The 2003 Accra Peace Agreement in Liberia required the transitional government to prioritize child combatants in its DDR plans. Similarly, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between Sudan and South Sudan set timelines for child soldier demobilization and family reunification.

A standout example comes from Sierra Leone, where the Lomé Accord involved UNICEF and other organizations in tailoring DDR efforts to the specific needs of child soldiers. This collaborative, child-centered approach should be the gold standard. Yet, as the research notes, many agreements still treat children as secondary beneficiaries of adult-focused DDR processes—a serious shortcoming.

Accountability and Justice

Perhaps the most sensitive issue is accountability. International law, including the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, recognizes the recruitment of children under 15 as a war crime. Yet holding recruiters accountable remains politically fraught.

Encouragingly, some peace agreements are making strides. Colombia’s 2016 Peace Accord, for instance, explicitly excluded child recruitment from the list of crimes eligible for amnesty. Similarly, the DRC’s Kampala Dialogue emphasized prosecuting those responsible for recruiting children.

However, accountability must also navigate complex ethical terrain. While the dominant narrative correctly views child soldiers as victims, there are growing calls to recognize their roles as perpetrators—particularly in cases where they commit serious crimes. The international community must walk a fine line: affirming the victimhood of children, while exploring non-punitive accountability mechanisms that acknowledge the harm caused, without undermining their rehabilitation.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite these advances, numerous challenges persist. Many peace agreements are the result of fragile political compromises, with parties often reluctant to admit to war crimes—including child recruitment. Where all sides in a conflict have used child soldiers, there’s often a shared reluctance to address the issue in peace agreements. Acknowledging it risks international backlash and complicates negotiations. As a result, parties may engage in a tacit “conspiracy of silence,” avoiding the topic altogether to protect themselves from accountability—at the cost of the children’s rights and long-term peace.

This silence must be broken. International actors, mediators, and civil society organizations have a critical role to play. The UN’s Practical Guidance for Mediators to Protect Children in Situations of Armed Conflict is a step in the right direction, offering concrete tools to ensure child protection is not left off the negotiating table. Moreover, child-specific provisions should be treated not as optional add-ons but as foundational to sustainable peace.

Peace agreements are more than ceasefire documents. They are a society’s first attempt to reimagine itself after the chaos of war. If children are to inherit a world worth living in, then peace agreements must reflect their rights, realities, and needs. That means ending the recruitment of child soldiers, supporting their reintegration, and holding perpetrators accountable. To do any less is to write a peace that is partial, and a future that is fragile.

@Peace News / Sean Molloy