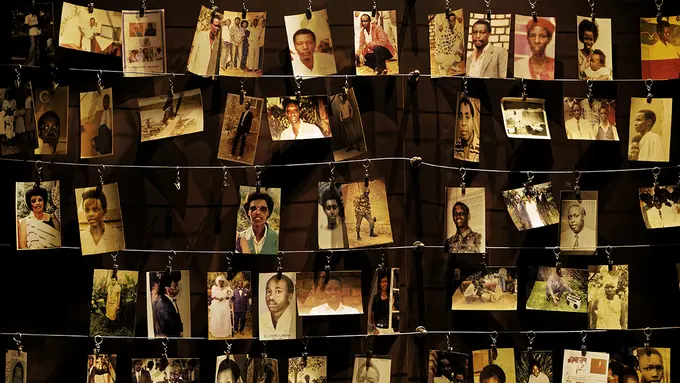

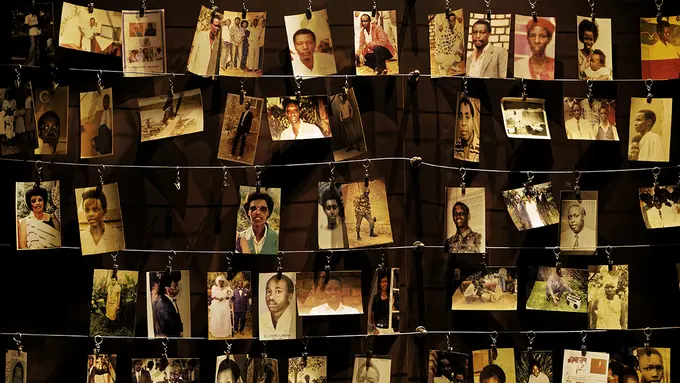

The Genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda lasted for thirty years not one hundred days

« “Genocide” Charge in Rwanda, U.N. Plans to Assist Refugees» ; « Rwanda Policy of Genocide Alleged » ; « Batutsi : Are they Victims of Genocide? » ; « Véritable génocide au Rwanda » ; « Sommes-nous complices d’un génocide ? »

These headlines do not date from 1994, but from 1964. The word genocide had been on the front pages of the international media three decades earlier to designate the attempted extermination of Rwanda’s Tutsi population. Thirty years is a short time, barely more than a generation. How can we explain the astonishment and the difficulty of almost all journalists, intellectuals and politicians in the West to qualify as genocide the 1994 cataclysm? We must admit that the acts of genocide perpetrated in the early 1960s were the object of a successful campaign of denial which continues to affect the world’s understanding of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi.

Denial was the condition for the maintenance in power of governments that pursued, with impunity, a policy of ethnic apartheid for three decades in which the deliberate massacre of a part of their population was always a foreseeable political option.

In a Belgian Security report of 9 December 1960, exhumed by the historian Léon Saur, an intelligence agent passed on the following note to Guy Logiest: “A member of Parmehutu declared to me that in the event of an attack by Tutsis from outside, the Hutus would first kill all the Tutsis living in the country”.

From the outset, the Parmehutu party that took power in Rwanda with the support of the Belgian authorities and the country’s highest Catholic hierarchy established anti-Tutsi violence as its major principle of political action. In November 1959, to hasten its takeover of the country, this party organized a campaign of violence and looting of the property of Tutsi families in the regions where the party was well established. Faced with this situation, the Belgian authorities placed the country under a state of emergency and entrusted the reins of the country to Colonel Guy Logiest. Fully empowered, the new master of Rwanda took up the cause of the rioters, dismissed the Rwandan administrative staff and replaced them with Parmehutu militants, encouraged the exile of Tutsi families abroad, organized the deportation of hundreds of them to retention zones inside Rwanda, banished the King of Rwanda from the territory, set up an exclusively Hutu Rwandan army, and in a climate of terror managed the process that led to the seizure of power by Parmehutu. The ultimate objective was to oversee the independence of the country under the control of a party and a president endorsed by the colonial power, Belgium.

Several archival documents show that, as early as 1960, the Belgian administration envisaged the possibility of a genocidal drift by Parmehutu, which would soon control all the wheels of power in Rwanda. In a Belgian Security report of 9 December 1960, exhumed by the historian Léon Saur, an intelligence agent passed on the following note to Guy Logiest: “A member of Parmehutu declared to me that in the event of an attack by Tutsis from outside, the Hutus would first kill all the Tutsis living in the country”.

Exasperated by the lack of reaction from his superior, the author of this note added in the margin, “The Special Resident has been briefed on this kind of thing. What does he do about it? Will he do anything about it? Do we have the right to know? Or does all of this disappear into the abyss of his unalterable self-confidence?” In fact, Guy Logiest was perfectly aware of the danger brought to his attention by his subordinate. The minutes of a conversation between the Special Resident and the Commissioner of the security department (Sûreté), M. Godard, held a month and a half later, on October 27, 1960, attest to this.

Commissioner Godard: “We must take into account the fact that an external intervention could help trigger an internal action, in the sense that terrorists trained outside could enter the country to cause trouble and provoke seditious movements among certain groups of the population at a given time.

Special Resident Logiest: “If such a movement were to arise in Tutsi circles, it would be a signal of their massacre by the Hutus. I think that the Tutsis are perfectly aware of this.”

On 28 March 1962, the local authorities mobilized and supervised their Hutu constituents to slaughter the Tutsis in their communes. The killings of 28 March 1962 can be legally considered as the first documented acts of genocide perpetrated by the government of the First Republic of Rwanda.

Not only were the Belgian authorities aware of the possibility of a genocidal drift on the part of Parmehutu, but some Belgian administrators helped to put it in place. This policy was officially called “large-scale reprisals” (« représailles à grande échelle ») in 1962. The decision to apply this policy for the first time was taken on 8 March 1962, after raids by Rwandan refugees from Uganda. This criminal option was decided during a special meeting that brought together the representative of the Minister of National Education Jean-Baptiste Rwasibo, the Belgian Territorial Agent Charles Lees, then Secretary-General of the Rwandan Ministry of the Interior, Lazare Mpakanye, the Prefect of Byumba Boniface Bashakira, and the burgomasters of the territory, who were advised by barwanashyaka (Parmehutu activists).

The bloodbath will take place on 28 March 1962. On that day, the local authorities mobilized and supervised their Hutu constituents to slaughter the Tutsis in their communes. Belgian Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Bruneau, who was present on that day, wrote: “Reprisals were carried out against the Tutsis of the entire Biumba prefecture. Atrocious scenes took place in all the communes where there was still a Tutsi. Teachers are snatched from their classrooms, taken a few steps away from the school and executed with machetes. Fathers of families, whose only complaint is that they are too tall, are immediately accosted, murdered and buried on the spot. Hundreds of huts are set on fire. All of these crimes have been perpetrated with such a concern for perfection and with such celerity that members of the UN circulating in this region on the day of the events were unable to notice anything.”

The killings of 28 March 1962 can be legally considered as the first documented acts of genocide perpetrated by the government of the First Republic of Rwanda. Of course, the Rwandan authorities presented the Byumba operation as a simple self-defence measure by the Hutus, and as a “spontaneous reprisal” perpetrated by Hutu peasants in anger after a rebel incursion, an argument that served as a leitmotif for all subsequent massacres of Tutsis. But the archives contradict this official version: the Byumba massacre and those that followed were anticipated, organized and supervised by the authorities. The defenceless victims were killed simply because they were considered Tutsi and not for what they had done, which in law constitutes the definition of the act of genocide.

The massacres at the end of December 1963 were on a much larger scale. In the prefecture of Gikongoro, the entire Tutsi population was targeted, and the accounts of the survivors of that time are similar to those of the survivors in 1994.

The following year, the massacres that followed the incursion of rebels into Bugesera at the end of December 1963 were on a much larger scale. This time, President Kayibanda sent his ministers to each of the country’s prefectures to supervise the anti-Tutsi “measures” to be taken locally. In Kigali, opposition leaders were arrested, sent to Ruhengeri and promptly shot. Roundups of Tutsis followed by summary executions that took place in Nyamata, Gahanga, Kigali, Rwamagana, Kibungo, Cyangugu… In the prefecture of Gikongoro, the entire Tutsi population was targeted, and the accounts of the survivors of that time are similar to those of the survivors in 1994.

Bertrand Russell denounced the “most terrible, systematic slaughter of people that we have seen since the Nazis extermination of the Jews in Europe,” but the tragic events of December 1963 and January 1964 quickly sank into oblivion and their genocidal nature was denied.

The genocide denial of 1963-1964 was successful

When the wave of violence took place in 1963-1964, no foreign press correspondents were present in Kigali. The international press did not send journalists until more than a month later: at the beginning of February 1964, sixteen reporters visited Rwanda, but by then the government had managed to stop the most visible anti-Tutsi violence.

At the end of December 1963, the then UN Secretary-General U Thant sent the diplomat Max Dorsinville to Rwanda to conduct a comprehensive report on the events. The UN special delegate was expressly chosen by President Kayibanda, who had refused to accept any other observer. Max Dorsinville stayed only a few days in Kigali, and was content to discuss with dignitaries of the regime and the Catholic Church and to record their versions of the facts. He did not meet with any

witnesses or survivors of the massacres. However, he organized a meeting with representatives of the diplomatic corps present in Kigali on 30 December 1964. During this working session, the representatives of the European states and the United States defined a common position that amounted to supporting the Rwandan government, regardless of the cost and consequences of such a decision.

The first articles on the events appeared in the newspaper La Cité, a Belgian Catholic organ that defended the regime of the First Republic and relayed the Rwandan government’s version of the events.

From the beginning of January 1964, a handful of courageous witnesses broke the omerta, called on international institutions, and secretly sent to the foreign press precise and documented accounts of the ordeal experienced by the Tutsis since Christmas. But it was not until the beginning of February that the newspapers Le Monde and Témoignage Chrétien finally relayed these first-hand accounts: that of the UNESCO agent Denis-Gilles Vuillemin, who kept a diary of the events and also meticulously collected testimonies from survivors, and that of the White Fathers of the missions of Cyanika, Kaduha, Mbirizi, and Nyamasheke, who sheltered survivors of the genocide in their missions. Thus, readers of the Christian press were able to read, for example: “On December 25, in the afternoon, a plan of repression began that consisted of the pure and simple extermination of all the Tutsi inhabitants of an entire prefecture, that of Gikongoro.

The entire Hutu population, Christians and pagans, catechists and catechumens, attacked the unfortunate Tutsis in bands of about thirty people, led by party “propagandists” with the blessing of the authorities. This time, the goal was not to pillage but to kill, to exterminate everything that bore the name Tutsi. To avoid possible humane reactions, the organizers of the massacres had avoided giving as a target the immediate neighbours of the Tutsis: one hill was busy killing the Tutsis of a distant hill and vice versa.

A few party informers remained on the spot. We missionaries have been shocked by the general silence of the radio and the international press. The embassies of Belgium, France, Germany and the United States in Kigali witnessed this tragedy and protested to the Rwandan government, but as embassies, they did not have to inform the international press. Would we Catholics be the last to leave this conspiracy of silence that makes us passive accomplices of this genocide?”

The testimonies published in reference press organs had the effect of a bomb. The minutes of the Belgian Council of Ministers of 7 February 1964 testify to the “concern” of the Belgian government at that time: “In view of the confused situation in this country [Rwanda] and more particularly of the accusations made against the Government of this State, would it not be appropriate for instructions to be given, through our embassy, to the Belgian technicians in Rwanda on the attitude to be adopted with regard to the operation underway to liquidate the ‘Tutsis’? As the affair is taking on an international dimension, we must be careful that Belgium is not accused of participating in a genocide’.”

The question of the qualification of the massacres of Tutsis as genocide is raised at an ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross] assembly, in the British and Swiss parliaments, as well as in the Church. This growing debate provoked new international investigations.

The UN report (on the Dec.1963/Jan.1964 killings of Tutsi) cleared the presidency of any responsibility for the massacres and minimized the number of victims of the massacres without any investigation.

The report of the commission of inquiry created at the request of the Swiss government, in response to the accusations of Denis-Gilles Vuillemin, and conducted under the supervision of the Prosecutor of the Republic of Rwanda, Tharcisse Gatwa, stated that the Rwandan state was responsible for the massacres through the direct involvement of no less than 89 people found guilty of crimes, including two ministers, local officials, prefects and mayors. But this report was not published.

Kayibanda refused to acknowledge its validity, and a new investigation was ordered. Not unexpectedly, the conclusions of the latter investigation were largely more favourable to the Rwandan government.

The UN once again sent Max Dorsinville to Rwanda. His second report was just as biased and indignant as the first. It cleared the presidency of any responsibility for the massacres and minimized the number of victims of the massacres without any investigation. The conclusions of this widely publicized report were taken up by the international press, which concluded, on the authority of the UN, that the term “genocide” was abusive to qualify the events in Rwanda, that the

number of victims claimed by witnesses had been overestimated, and that the Rwandan government had done everything possible to pacify the country.

The most serious investigation of the massacres in Rwanda was carried out by an ICRC team that spent several weeks in the country, visiting all areas of the country, interviewing witnesses as well as authorities and visiting prisons. This report confirms in all points the accounts and reports of the priests of the missions of the prefectures of Gikongoro and Cyangugu, as well as that of Denis-Gilles Vuillemin who had denounced the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi. But in accordance with the status of the ICRC and its commitment to neutrality in conflicts, this report was not communicated. It remained confined in the organization’s archives and could not be used to establish the truth. When I went to read it in Geneva in 2019, the ICRC archivist informed me that I was the second person to consult it since its reading had been made possible.

The shaking of the Catholic Church and the Christian community by the revelations of the missionary priests who had helped the survivors of the massacres did not last. The head of the Church of Rwanda, Bishop Perraudin, used his authority and connections to discredit and silence the missionaries who had denounced the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis of Rwanda.

He disseminated in the Catholic press a watered-down version of the events and shamelessly suggested that to stop supporting the government of Rwanda would be the “real genocide”.

This is how genocide denial cloaked the reality of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis of Rwanda in December 1963 and January 1964 with a veil of lies and silence. In Rwanda, the Tutsi survivors could not make their voices heard, otherwise they were eliminated. Outside Rwanda, the survivors’ stories were of no interest to anyone. The international community, and more precisely the Western camp, chose to continue to support a Rwandan government whose genocidal baseness

were common knowledge but which, in the context of the Cold War, had the advantage of having written into its constitution a ban on all communist activity and propaganda. The lesson is that a successful genocide denial campaign sets the ground for recurrence. In the case of Rwanda, the denial of the successive anti-Tutsi genocidal pogroms emboldened perpetrators and enabled a foreseeable genocide in 1994.

@The Panafrican Review