Can Africa’s Liberation Movements Survive the Gen-Z Era?

Many African political parties born out of liberation struggles are currently grappling with how to ensure continuity. While these movements once commanded deep legitimacy rooted in sacrifice and historical purpose, sustaining relevance across generations has proven to be an existential challenge. The political consciousness and expectations of younger generations, particularly Generation Z, are markedly different from those of the liberation era. Consequently, several once-dominant parties across the continent are facing profound structural, ideological, and legitimacy crises.

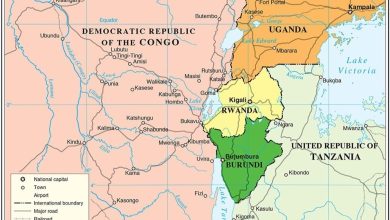

Across the region, the pattern is increasingly familiar. In Tanzania, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) is under growing pressure to respond to Gen-Z demands that are louder, digitally mobilized, and less deferential to liberation credentials. Young Tanzanians are increasingly impatient with unemployment and governance systems that appear slow or distant.

In South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC), once the undisputed symbol of moral authority, is widely viewed as being in a state of political crisis. Internal factionalism, corruption, and weak service delivery have eroded its standing, especially among younger citizens who no longer feel bound by the loyalties of their parents.

Uganda offers another instructive case. The National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power in 1986 with a reformist agenda that restored stability and rebuilt institutions. However, over time, the movement has become increasingly personalized. The absence of a nurtured succession culture raises serious questions: when the founding leadership eventually exits, does the NRM risk fading into history because it failed to institutionalize leadership beyond an individual?

The trajectories of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Ethiopia and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement(SPLM) in South Sudan serve as further warnings. The TPLF’s loss of central power illustrates the danger of failing to adapt to new national pluralism, while the SPLM’s fragmentation into ethnic conflict underscores a harsh truth: liberation alone does not produce governance. These qualities must be deliberately cultivated.

Against this regional backdrop, the experience of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF-Inkotanyi) stands out for its deliberate focus on political education and institutional renewal. Unlike many of its counterparts, the RPF invested early in a party culture that extended beyond elections and personalities.

This continuity was nurtured through early socialization. Growing up as a refugee I remember our parents attending RPF monthly membership meetings on every last Saturday evenings of the month under trees, classrooms or community centers. Here values were reinforced, and collective responsibility was cultivated. During secondary school, junior cadre schools exposed young people to ideals of patriotism, discipline, and service. This ensured that party values were transmitted across generations rather than being rediscovered during moments of crisis.

The RPF’s emphasis on continuity has recently evolved through significant institutional reforms, most notably the proposal of the Council of Elders and a strategic expansion of the party’s leadership structure. The Council of Elders is designed to safeguard institutional memory and provide moral guidance, ensuring the RPF remains anchored in its founding values while deliberately creating space for younger leaders to operate. Complementing this, reforms adopted during the 17th Congress, including the addition of a second vice-president and a deputy secretary-general, reflect a move toward a more resilient and responsive organizational framework capable of managing future transitions with stability and foresight.

During these reforms, the party leadership’s message was clear: institutional leaders must listen more, consult more, and become more accessible. President Paul Kagame reinforced this by stating that the party cannot operate as it did 35 years ago. This acknowledgment is critical; many liberation movements fail because they treat their founding moment as a permanent blueprint rather than a starting point for evolution.

These reflections are sharpened by recent Gen-Z uprisings across Africa. Protests driven by the cost of living and unresponsive institutions reveal a widening gap between traditional leadership and younger citizens. The fundamental question emerges: Why should young people have to take to the streets for their voices to be heard?

Protests are often not a rejection of the state, but a response to closed systems. When political movements lose the ability to engage meaningfully with the youth, pressure inevitably spills into the streets.

Continuity does not mean stagnation. For liberation movements to remain relevant, they must invest in intergenerational dialogue and institutional reform. The RPF experience suggests that a guided transition, rooted in early socialization and a willingness to adapt, offers a viable alternative to the decline witnessed elsewhere.

In an era where historical narratives carry diminishing weight, the real test for Africa’s liberation movements is not how well they defend their past, but how effectively they prepare for the future.

The writer (via his LinkedIn account), is Dr. Joseph Ryarasa the Executive Director and Co-founder of Never Again Rwanda. He is A medical doctor with extensive experience in the clinical practice, Public Health, Peace Building and Human Rights.