How Organized Crime Threatens the Amazon’s Uncontacted Tribes

Organized crime has become an existential threat to the uncontacted Indigenous peoples of the Amazon as illegal gold miners, drug traffickers, loggers, and poachers advance ever deeper into the world’s largest rainforest.

The Amazon basin is home to around 95% of the Indigenous people living in isolation, with an estimated 124 groups living in Brazil alone, according to a recent report by Survival International, a non-governmental organization that works with Indigenous peoples around the world. Although commonly referred to as uncontacted, all are aware of the outside world, and most have had some kind of contact with it but choose to live in isolation.

The regions with the highest concentrations of these communities have become prized territories for criminal networks and armed groups, offering access to lucrative illicit resources and opportunities to conduct operations far from the reach of authorities.

Some of these criminal actors are sophisticated and powerful armed groups, like Brazil’s Red Command (Comando Vermelho – CV) and First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), which operate across Brazil’s Amazonian border regions, or Colombian guerrilla groups such as the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) and dissidents of the demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), which occupy territory encroaching on Indigenous lands in both Colombia and Venezuela.

Others, though, are illicit laborers, local residents, and economic migrants seeking an escape from extreme poverty through opportunities offered by the criminal entrepreneurs who bankroll and coordinate the sacking of the jungle.

All of these actors represent a potentially deadly threat to the uncontacted. Criminal operations in particular destroy or contaminate the ecosystems on which they depend and cut them off from access to the lands they need to sustain their nomadic way of life. Moreover, outsiders can bring diseases against which the Indigenous communities have no immunity, and their presence can disrupt these communities’ autonomy and culture, Survival International’s Teresa Mayo told InSight Crime.

“Their lives are based on the relationship with their territory. If they lose their access to their territory or the quality of their forest because it is contaminated, then their survival is at risk,” she said.

The advances of criminal groups and their labor force into territories of uncontacted Indigenous groups have also led to deadly confrontations, although cases are only usually documented when there are casualties on the criminal side.

“We never know how many uncontacted people have been killed because that’s the side we never see,” Mayo said. “But we should not forget that it’s arrows against bullets.”

Drug Trafficking in the Depths of the Amazon

The largest concentration of uncontacted peoples in the world live in the border region between Brazil and Peru, which in recent years has become a key drug production and trafficking territory. While trafficking in the region has long been the preserve of local crime clans and independent networks, multiple reports point to a growing role for Brazilian groups such as the Red Command.

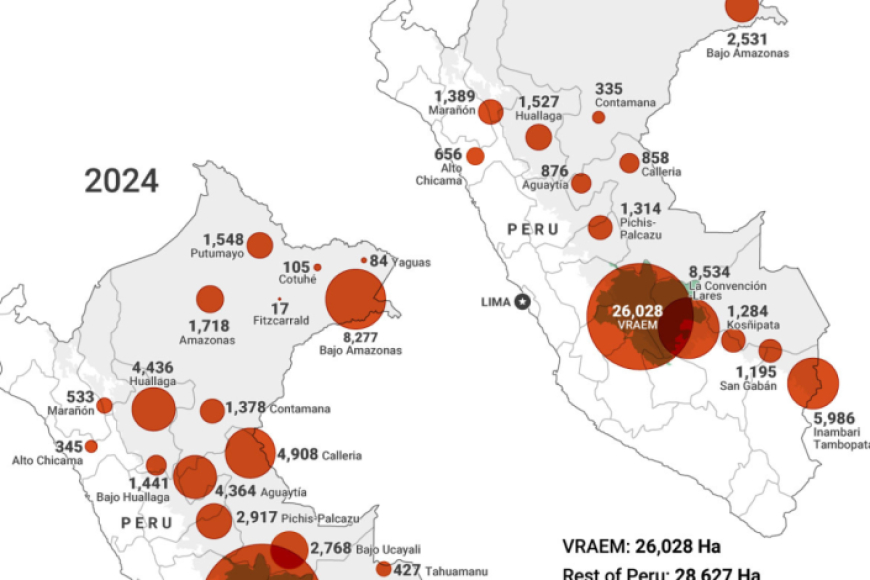

Coca cultivation in the five Peruvian departments that have territorial reserves for Indigenous people living in isolation or in a phase of initial contact has increased by 87 percent since 2019, reaching 44,211 hectares in 2024, according to crop monitoring carried out by the country’s anti-drug agency. Much of this cultivation is concentrated in the department of Ucayali, whose shared border with the Brazilian state of Acre is home to numerous uncontacted groups.

To process and transport coca, trafficking networks set up rudimentary labs, which dump toxic byproducts, and cut airstrips into the forest. But deforestation and contamination are only part of the impact on Indigenous communities. The presence of trafficking networks has also sparked violence.

Peru has seen a spate of killings of Indigenous leaders who have denounced drug trafficking. One of the peoples most affected has been the Kakataibo, who lost at least six leaders to criminal violence between 2020 and 2024. A branch of the Kakataibo continue to live in isolation, and while this means they are not targeted for speaking out, they are still living under the threat of drug violence, Herlin Odicio, a Kakataibo leader from Ucayali, told InSight Crime.

“They can run into a group of coca growers or drug traffickers and end up in a confrontation, and then they exterminate them,” he said.

Threat of the Amazon Gold Rush

The fastest growing criminal threat in many of the uncontacted people’s lands is illegal mining, which is spreading across the Amazon in a boom driven by sky-high international gold prices.

Carried out with backhoes that tear down trees and dredges that churn up rivers, mining drives deforestation and degradation of forests and pollutes water and food supplies, especially from the mercury used in processing. It also generates violence, as armed groups and local prospectors alike protect their interests at the point of a gun.

Miners “are destroying these territories, they are destroying the forests, destroying nature, destroying the rivers,” said Odicio.

The most urgent threat is in Yanomami Indigenous territories in the Brazil-Venezuela border region, where villages of an uncontacted people known as the Moxihatetema have been identified just kilometers away from illegal mining sites.

The region has long been invaded by thousands of illegal miners known as garimpeiros. InSight Crime investigations have revealed how today, garimpo operations frequently work with the support, supervision, or protection of the PCC on the Brazilian side of the border and corrupt elements of the military in Venezuela.

Over the past year, environmental and Indigenous organizations have also sounded the alert about the expansion of mining into uncontacted Indigenous territories in Colombia and Ecuador.

In Colombia, environmental watchdogs have detected the presence of numerous gold dredges inside the Rio Puré National Park, a protected area home to Yurí–Passé communities living in voluntary isolation.

There have also been reports of illegal mining operations in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park, which is home to the country’s last remaining uncontacted tribes: the Tagaeri, Taromenane, and Dugakaeri. Leaders of the related Waorani people blamed the incursion on the Choneros, one of Ecuador’s most powerful criminal organizations.

The Amazon’s Voiceless Victims

While drug trafficking and illegal mining represent the biggest draw for powerful organized crime groups, uncontacted communities are also at risk from networks far down the criminal food chain, which pose just as much of a threat to their survival.

Activities such as timber and wildlife trafficking take a heavy toll on the way of life of uncontacted people, depleting the game and degrading the habitats they rely on for their sustenance. Efforts to repel loggers and poachers from their lands can turn violent.

SEE ALSO: The 3 Biggest Threats to Indigenous Communities in Peru’s Amazon

In both cases, loggers and poachers are often members of local communities, who see hunting and logging as among the few economic opportunities available to them. However, they are often just the visible face of complex networks of financiers, brokers, logistics networks, and legal businesses that launder illicit products into legal supply chains both nationally and internationally.

The interests behind these networks are often powerful players in the legal economy, who can often count on local and even national political protection and support. These actors represent another face of the criminal threat to uncontacted peoples: the intersection between organized crime and the legal economy.

Threatened by such powerful interests while living in isolation leaves these tribes uniquely vulnerable, said Odicio, the Kakataibo leader from Ucayali.

“They have no way to defend themselves,” he told InSight Crime. “They can’t protest or talk to the state, they live in the forest. That’s why the only alternative is for us ‘civilized’ Indigenous people, as they call us, to protect these territories.”

Source: Insight Crime