Somalia’s Fragile State Faces Growing Risk of Jihadist Takeover

Somalia is approaching a critical tipping point. Deep political fragmentation, a faltering security architecture, and growing regional rivalries are converging to create the most serious threat to the country’s survival as a federal state in more than a decade. Without urgent political course correction, Somalia could slide toward state collapse—or an outright takeover of Mogadishu by the al Qaeda–linked militant group al Shabaab.

That is the central warning of a new analysis by Matt Bryden, a strategic adviser and founding partner of Sahan, a Horn of Africa–focused security and policy research center. Bryden argues that al Shabaab’s resurgence is less a reflection of the group’s strength than of Somalia’s accelerating political dysfunction.

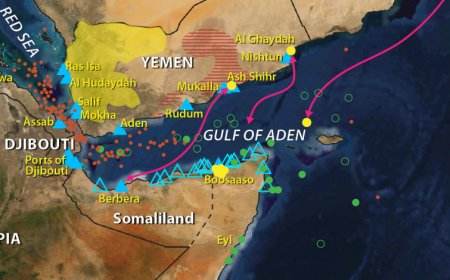

Although Somalia’s federal government enjoys international recognition and billions of dollars in donor support, its actual control is narrow. In practice, Mogadishu governs little more than the capital and a handful of surrounding towns, while al Shabaab controls or contests large swaths of central and southern Somalia.

After a short-lived military offensive in 2023 pushed militants out of parts of central Somalia, government momentum collapsed. By mid-2025, al Shabaab had recovered most lost territory and advanced to within 50 kilometers of Mogadishu, briefly encircling the capital. Foreign embassies quietly evacuated nonessential staff, underscoring growing concern that the city could fall if the offensive resumes.

Somalia’s national army remains heavily dependent on external support, particularly from the African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). Yet donor fatigue and political interference from Mogadishu have weakened the mission, raising the prospect of a drawdown that could leave the capital dangerously exposed.

Federalism Under Strain

At the heart of Somalia’s crisis lies a breakdown of its fragile federal settlement. Since the adoption of a provisional constitution in 2012, relations between the federal government and powerful regional states—especially Puntland and Jubaland—have steadily deteriorated.

Bryden notes that successive presidents have sought to centralize power in Mogadishu rather than negotiate power sharing, despite constitutional ambiguities that require consensus between federal and state authorities. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s current efforts to amend the constitution and introduce a new electoral system are widely viewed by critics as attempts to extend his rule beyond the end of his term in May 2026.

These moves have deepened polarization and paralyzed cooperation against al Shabaab. Puntland and Jubaland have suspended relations with the federal government, while opposition groups warn that unconstitutional term extensions could trigger violent unrest in the capital—a scenario that would only benefit jihadist forces.

The paper also highlights Somalia’s steady drift toward illiberal, Islamist governance. While Somalia historically combined Islam with largely secular state institutions, the current constitutional framework embeds Shari’a law more deeply into the political system.

Mainstream Islamist movements—some linked to the Muslim Brotherhood or Salafi networks—now dominate Somalia’s political landscape. Bryden cautions that hopes al Shabaab might be integrated into governance through negotiations are dangerously misplaced. The group’s ideology, he argues, points clearly toward a rigid theocracy resembling Taliban rule rather than a constitutional Islamist model.

Regional Powers Raise the Stakes

Somalia’s internal crisis is further complicated by intensifying regional competition. Middle Eastern powers, particularly Qatar, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates, are backing rival Somali actors in line with their broader geopolitical and ideological interests.

Qatar and Türkiye generally favor a strong, centralized Somali state under Islamist leadership, while the UAE, along with Ethiopia and Kenya, has supported more decentralized federal arrangements and close ties with regional administrations such as Somaliland and Puntland. This rivalry risks turning Somalia into another arena for proxy competition, deepening divisions rather than resolving them.

Bryden pays particular attention to Somaliland, which has functioned as a de facto independent state since 1991. As Somalia’s instability worsens, more international actors may reconsider Somaliland’s long-standing case for recognition—especially if Mogadishu were to fall to al Shabaab.

In a worst-case scenario, Bryden argues, Somalia’s regional states could form a provisional authority outside Mogadishu to contain jihadist expansion, backed by neighboring countries. Such an outcome would mark a dramatic failure of Somalia’s post-2012 state-building project.

A Political, Not Military, Solution

Despite the grim outlook, the paper stresses that Somalia’s fate is not sealed. Al Shabaab, Bryden argues, cannot be defeated by military means alone. What is urgently needed is a government of national unity, renewed trust between federal and state leaders, and a return to consensus-based constitutional politics.

“The greatest asset of the anti–al Shabaab forces,” Bryden concludes, “is not their combined military power, but the promise of a better life than under jihadist rule.”

Without that political vision, Somalia risks drifting into a darker chapter—one defined not just by violence, but by the collapse of the fragile federal experiment meant to hold the country together.